Shifting lines of battle: How to work out solutions to conflicts that travel between and inside organizations?

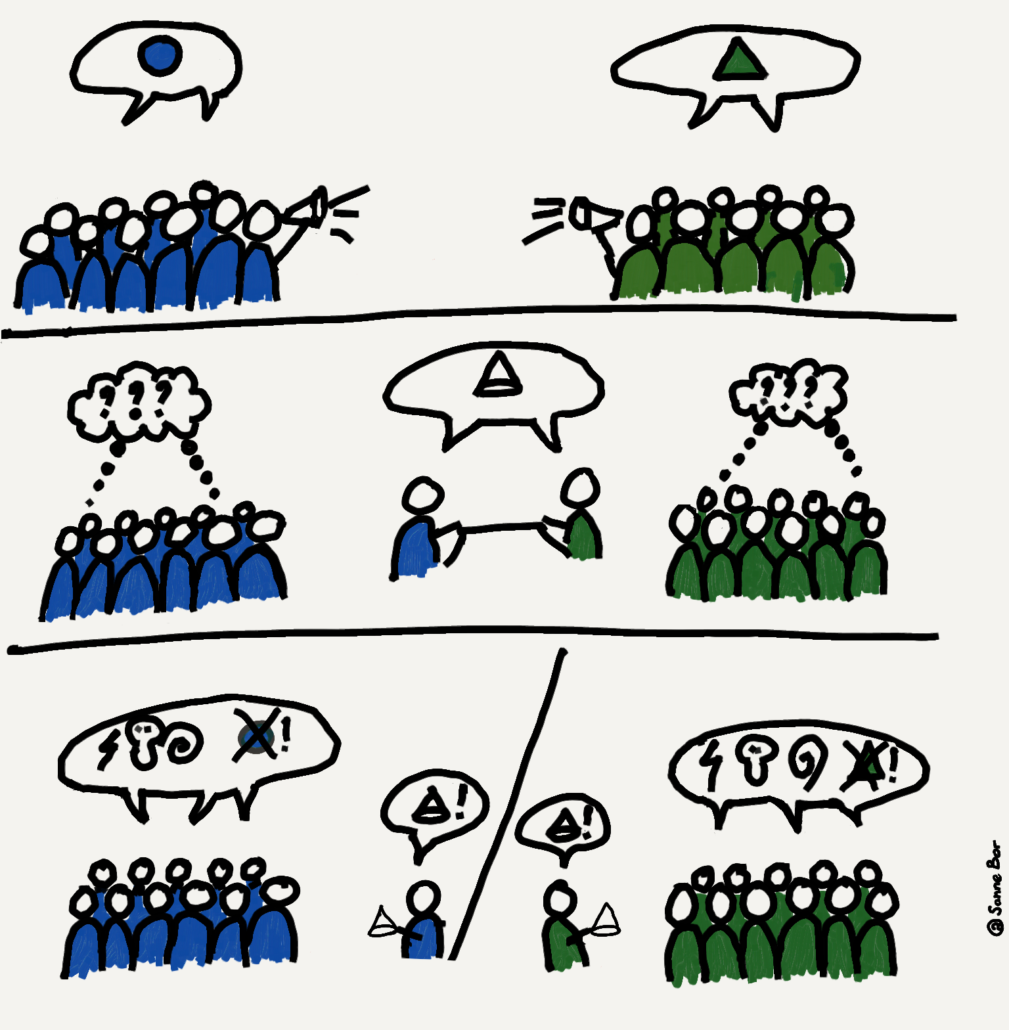

One key challenge in environmental conflicts is to get interest organizations to the same table to work towards a solution that gets them over their potentially long-term tensions. However, when they agree to this, there are plenty of further challenges on the road to find collaborative solutions that would be widely accepted. We highlight one such challenge: how representatives of interest groups manage to keep their organizations committed to the process when the mission is to find common solutions between interest organizations.

Collaborative governance is based on the premise that people participating in collaborative processes learn from each other and thus build capacity for joint problem solving. While participants of collaborative processes learn to know one another they also learn to trust each other. They learn to see the issue at hand as a complex problem that can be grasped from different angles. They learn to understand the challenges or issues that matter to the other participating organizations in the complex problem. These insights make it possible for the participants to start looking for solutions which bring mutual benefits.

The learning process which participants of collaborative processes go through is hard to share with those who have not been part of the process. A learning process is always emergent and not decided or foreseeable. Its steps as well as outcomes are difficult to articulate, and they may become as a surprise. Therefore, they may be difficult to mobilize within the interest group that has been part of the process through its representative. In addition, learning to understand other stakeholders’ perspectives might not be included in the “assignment or contract” made between the interest group and its representative. On the contrary, the representative’s mission might be solely to deliver the demands of the interest group at the table and bargain to gain a best result serving the interest.

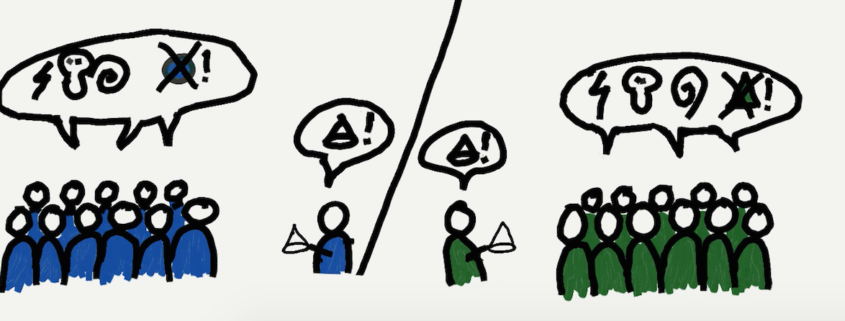

Maintaining the trust from their own organization or group may thus become an issue for the representatives at the negotiation table. When the legitimacy of representatives is reducing and trust in them fades this also disrupts or at least complicates the collaborative process among interest groups. Trust can quickly erode when those at the table are unable to communicate what has been learned and how these learnings benefit the interest group. Particularly, when trust in the other organizations at the table is low, members in the interest organizations may not see the value of negotiated compromises or the need to find a shared solution. As a consequence, nascent agreement and amity may shift the conflict from between the organizations to inside the organizations.

There are two possible outcomes of the misalignment between representatives and the organization they represent:

- The organization rejects the possible solutions and walks away from the table, leaving the conflict to simmer on, possibly with more fire than before. Walking away from the table can hurt the trust that was created during the process and make future attempts to resolve the conflict even more difficult.

- The organization does sign up for the deal, but the organization gets into an internal legitimacy crisis as some members of the organization do not feel heard or even betrayed, believing the organization has not taken care of the issues they were fighting for. Inside an organization, the conflict may be difficult to address and manage, particularly, because the debate does not anymore take place in open but closed fora. If the internal power battle leads to more extreme views taking over within an organization, it becomes ever more difficult to resolve the conflict between organizations.

There are steps that can help to avoid the highly dysfunctional eroding of trust between interest groups and their representatives.

- To prevent internal tensions to distract the whole process, make sure enough resources and tools are available to organizations’ internal communication. Internal communication ensures that everybody understands why there is a collaborative process and what it aims at. In addition, internal communication is essential for the members to reflect collectively on what they want to achieve, and why their goals may need to be renewed and updated during the process as learning takes place. It may also be important to clarify what kind of process the collaborative process is, what this process demands from the organization (e.g., rules and expectations), and the types of outcomes for all parties (including the principle that all will benefit and the idea that a benefit gained by one organization is not necessarily a loss for the others). Furthermore, when there is a lot of distrust and old hurt within the organization towards the other organizations, it is of vital importance to build internal processes that ensure people get heard, get to express their concerns and get the possibility to understand what is done with their concerns. Finally, the representatives of organizations should be actively encouraged to share and communicate the insights gained during the process with the organization members at different steps along the process. Giving a blank check or a very restrictive mission are both dysfunctional. Having clear feedback loops during the process and new agreements on what is aimed at may help the members of the organization stay on track and raise concerns when they arise.

- While each of the organizations need to deal with the existing old hurt and distrust internally, this work also needs support from the other organizations at the table. If all organizations are going through internal struggles which potentially lead to more extreme views taking over, the parties drift further away from each other, with severe effects on their collaboration. Representatives of the organizations need to be encouraged to discuss the internal tensions they face. Having a clear shared approach and agreements that aim to ensure the trust in one another is growing instead diminishing can be helpful. This may include an agreed communication strategy and a process for agreeing on the exact messages to be send out. It may also include designing a broader set of interactions among the organizations to encourage also the members to engage in the collaborative process.

Sanne Bor, Taru Peltola & Outi Ratamäki

Sanne Bor works as Researcher at Hanken School of Economics, for the CORE project, and at LUT University, for the PackageHeroes project. She studies collaboration among organizations.

Taru Peltola is an Associate Professor of social sustainability at the University of Eastern Finland and Finnish Environment Institute. She leads the CORE-project’s case study work package.

Outi Ratamäki works as a senior lecturer at the Law School, University of Eastern Finland. She studies natural resources governance at the crossroads of law.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!